Donald Teague Biography 3 (1930's)

Professionally, the story of Donald Teague in the 1930’s is one largely of working for Crowell-Collier’s during the Great Depression, establishing his bona fides as a fine artist, and experiencing renewed prosperity in 1937 with emergence from The Great Depression and regaining work with The Saturday Evening Post.

The Crowell-Collier’s publishing empire included three prominent magazines: Collier’s Weekly, Woman’s Home Companion, and The American Magazine. Each was directed at a different audience, and accordingly ran different types of stories. Westerns were largely the domain of Collier’s. Teague illustrated for all three magazines, beginning with The American, then Woman’s Home Companion, before he finally appeared for the first time in Collier’s in September 1930.

As was the case with The Post, for the first several years, Teague did not illustrate many westerns for Collier’s. Teague’s breakthrough western Collier’s assignment came in in 1936 when he illustrated the ten-part Trouble Shooter, written by the revered western author Ernest Haycox. Teague would go on to illustrate a number of Haycox stories and serials.

Biographic information about Teague often suggests that he was first an illustrator, then became a fine artist in 1956 when he stopped illustrating. The truth is, Teague always had ambitions as a fine artist, and was keen to not become pigeon-holed as being merely an illustrator. From early in his career Teague entered top fine art juried competitions. Teague first showed at the National Academy of Design (NAD) in 1928, and won his first award in 1932. He continued to show at NAD until 1972, and he garnered a number of additional NAD awards including many first prizes. Teague first showed at the American Watercolor Society (AWS) in 1933, four years after taking up the medium. He gained his first of numerous awards including several first prizes at AWS in 1944. Teague continued to show at AWS until 1977.

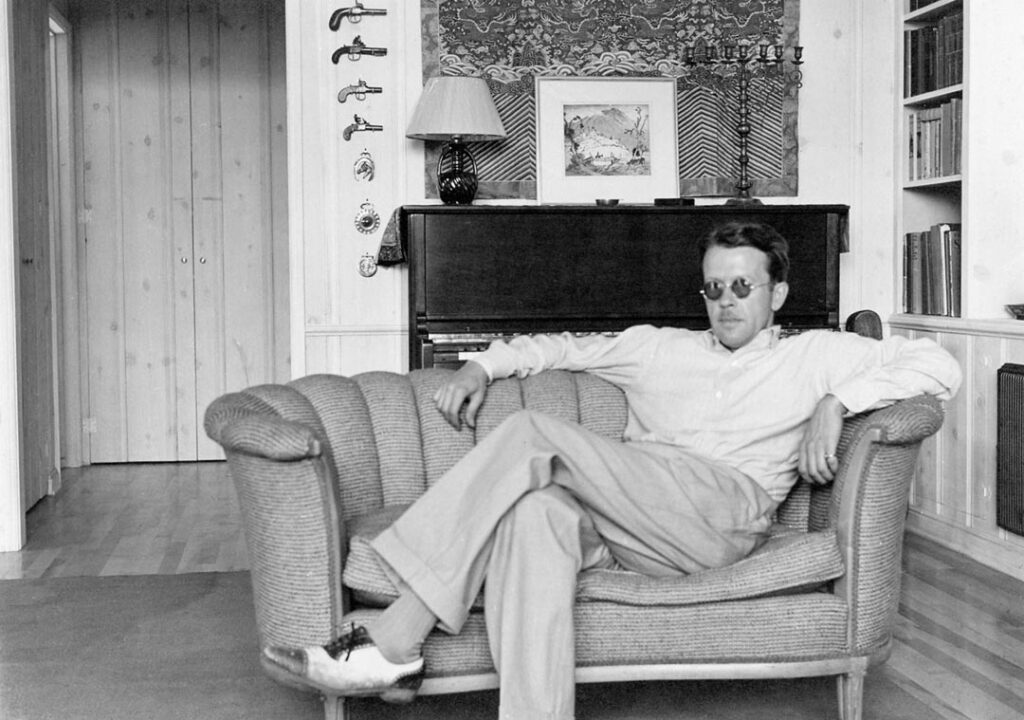

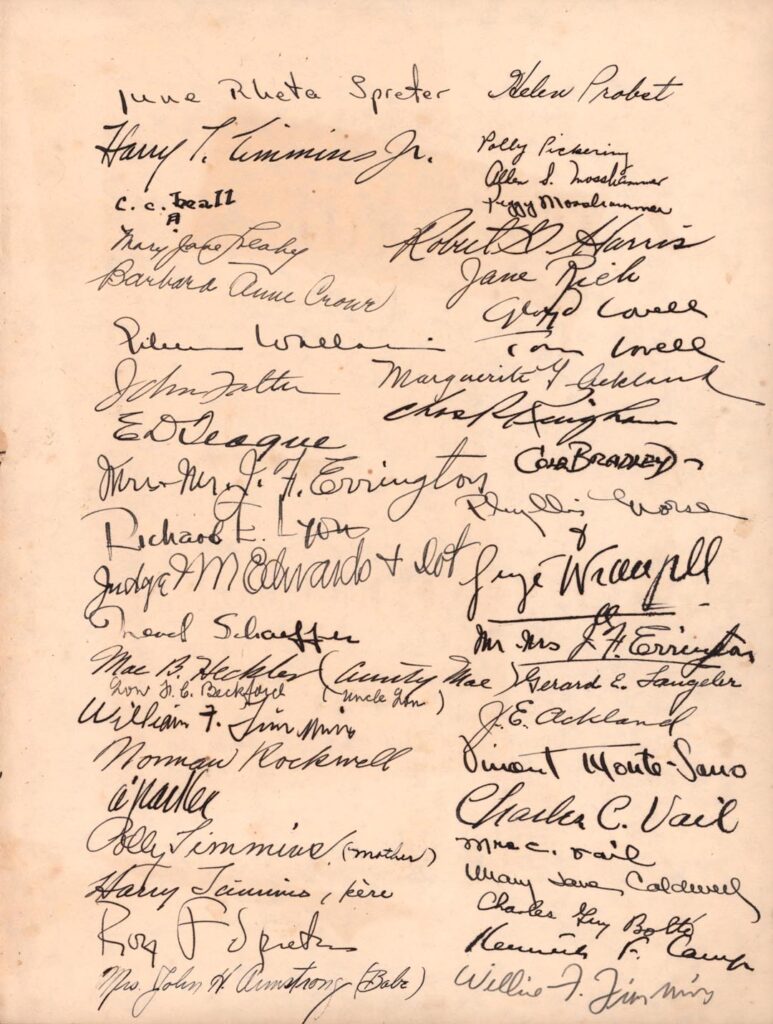

Teague’s personal life took a number of positive turns in 1938. He met young Verna Mae Timmins at a party thrown by John Falter. Falter was working in advertising at the time, but went on to become a top Post cover artist. Verna was the daughter of Harry Laverne Timmins, a well-known illustrator and a co-founder of the American Academy of Art in Chicago. It is possible that Donald and Harry knew each other prior to Teague meeting his daughter Verna, as they both illustrated for Collier’s from 1930 on. Donald and Verna wed in July 1938. Local newspaper coverage of the marriage provides a fascinating glimpse into attendees and the series of parties that surrounded the wedding. The back of the marriage certificate was signed by attendees and reads like a who’s-who among top illustrators – Norman Rockwell, Al Parker, Mead Schaeffer, John Falter, C.C. Beall, Roy Spreter, Tom Lovell and Harry Timmins were all in attendance.

After honeymooning in Cape Cod, the couple headed west to Los Angeles to join Edwin and Jack Teague, who had already moved to California. A natural pause in Teague’s artistic output occurred relative to these events. After renting a home in the Hollywood Hills, Donald and Verna bought a home in Encino. They lived in Encino until 1949.

One established in Los Angeles, Teague resumed work as an illustrator. Teague rekindled relationships with artist friends who had moved west before him, including Bernard (Ben) Herzbrun and William (Bill) Menzies. Both men worked as art directors in the film industry. Menzies was a former classmate at Art Students League. In 1939, Herzbrun was working at 20th Century Fox. He would go on to work with RKO in the 1940’s, then Universal Studios where he eventually became head art director. In 1939, Menzies was working with Selznick International and United Artists, including on the film Gone With The Wind. Menzies went on to work with RKO in the 1940’s. These friends, and perhaps others, opened a new world for Teague – that of the film industry, during its Golden Age no less.

The film industry and Teague shared a trait in common: they were both sticklers for authenticity. To ensure public acceptance (to include that of subject matter experts), everything in period films had to be historically accurate – sets, costumes, props etc. To meet this objective, considerable research went into everything that was ultimately seen on the silver screen. Via his friendships, Teague was able to gain access to period movie resources to help make his illustrations. On a western assignment for example, Teague could utilize sets, costumes, horses, rolling stock, saddles, firearms – the works. As a result, Teague’s accuracy and realism as an illustrator accelerated with the move to Los Angeles.