Donald Teague Biography 2 (1923-1930)

For the 25-year-old Teague, starting work for The Saturday Evening Post must have been both an exciting and a humbling experience. During the 1920’s, cover artists included Norman Rockwell, J.C. Leyendecker, E.M. Jackson, Ellen Pyle, and Alan Foster. Inside illustrators included Anton Otto Fischer, Tony Sarg, and W.H.D. Koerner. It was one of The Post’s many golden eras within the golden age of illustration – and Teague was in the thick of it.

Soon after starting with The Post, Teague moved from Manhattan to New Rochelle, in Westchester County. New Rochelle had a thriving artist colony popular among actors, writers and visual artists. Led at the time by J.C. Leyendecker and Norman Rockwell, Teague’s community of fellow illustrators in New Rochelle included C.C. Beall, John Clymer, Tom Lovell, Edward Penfield, Al Parker, and Mead Schaeffer. Of life in New Rochelle, Teague said:

There were 18 ranking illustrators in that town at one time, topped by J.C. Leyendecker and Norman Rockwell. They were the only group of artists I’ve ever been with that never had an argument.

Unlike many of The Post’s illustrators, Teague never worked exclusively for The Post. He continued to illustrate for the Elks Magazine until 1929, and illustrated for Liberty Magazine from 1924 to 1928.

Teague’s illustrations from the 1920’s give little indication of what would follow later in his career, either stylistically or thematically. Teague worked in oil at this time. Although Teague is remembered mostly for his westerns, most of his assignments for The Post during the 1920’s were not westerns. Common themes during this period include high society, boy-meets-girl, nautical, and aviation scenes. Of the 63 Post stories that Teague illustrated during this period, 9 could be considered westerns. W.H.D. Koerner was a powerhouse western illustrator for The Post during this period, so it is likely that The Post directed important western stories to him.

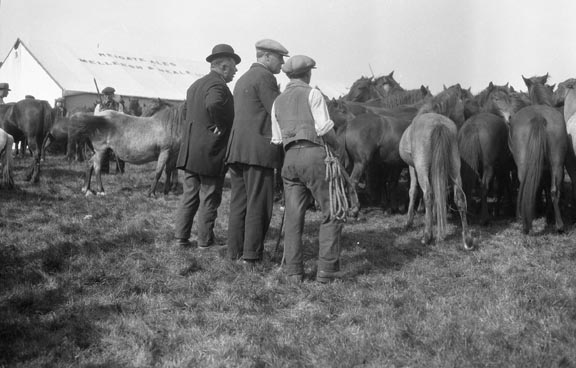

During the 1920’s, Teague developed skills and interests that would feed into his ultimate mastery of the western illustration genre. Teague was keen to develop his ability to illustrate horses. Teague travelled to England five separate years during the 1920’s, in part to photograph and sketch the horse fairs as he followed them through the countryside. Teague

studied intensely the works of Sir Alfred Munnings, England’s famous horse painter, and purchased a number of Munnings’ books and catalogs. Although Teague attempted to meet Munnings, there is no record that the two men met. When

in London, Teague continued his art studies under both Sir Frank Brangwyn, a prolific jack-of-all-trades remembered mostly as a muralist, and Norman Wilkinson, the renowned maritime watercolorist. Wilkinson taught Teague a considerable amount about watercolor painting, and both men provided him with valuable input and criticism.

During multiple summers in the 1920’s, the Teague family returned to the Mandal cattle ranch in Yampa. The ranch, remotely situated on the western slope of the Rockies, provided an ideal setting for sketching and working. Ranch hands provided additional subject material and many colorful stories. Jim Alfred, an old-timer and the owner of the ranch, had started on the trail as a cook’s helper at the age of nine. Around the fireplace, Alfred regaled the Teagues with his first-hand stories of

settling the frontier. Although five feet eight inches tall and of slight build, the warm and modest young artist

from Flatbush developed a binding affinity for the rough-and-tumble Old West through these experiences.

In his 1970 memoir Edward’s Odyssey, Edward Gallahue, a first cousin to Teague, provides an account of one trip to Yampa during the summer of 1923. Edward and his brother Dudley founded the highly successful American States Insurance Company based in Indianapolis. Edward in particular became a pillar of the community. Covering diverse topics including business, philanthropy, mental health (Edward’s mother Pearle suffered from profound depression), and theology, the memoir is an interesting read. At any rate, Gallahue writes:

At about this time, my uncle Edwin Teague of New York City retired… and wrote that he was going to spend the summer on a cattle ranch in Colorado. Since his two sons, my two first cousins, were to be with him, he invited me to go along…. Donald was already a successful commercial artist, illustrating books and stories in magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post.

… Yampa, located in northwestern Colorado, was a little frontier town with unadorned frame buildings. It was set in a broad valley with mountains rising on either side. When I arrived, I was met by Uncle Ed, Jack, Donald, and Tom Alfred, the owner of the ranch.

… The ranch house was the center of activity in the evenings and the scene of conversation, both outlandish and serious, on many subjects… Donald, of course, was interested in his art and in reading the stories he illustrated, and sparked the conversation with lively comments about the various magazine stories and their authors.

Everything seemed to be coming up roses as Teague entered 1929. Then, economic conditions began to deteriorate, with the Great Depression officially beginning later in the year. Based on my review of various popular magazines, advertising and the associated revenue began to decline precipitously many months prior to the official start of the Great Depression. The Saturday Evening Post was forced by economics to make some hard decisions. One of those decisions was to let younger illustrating talent go, so as to concentrate work in a core stable of more senior illustrators. Teague was one of the casualties of this move. Teague went from having 14 completed Post assignments published in 1928, to 12 in 1929, to 2 in 1930. He would not appear in The Post again until 1937.

It is conjecture on my part, but I suspect that Teague was told by The Post that he would be let go many months prior to being cut – perhaps in mid 1929 – so as to provide time to line up other work. In the summer of 1929, Teague made another trip to England, but started working in watercolor for the first time. Illustrating in watercolor was advantageous as it reproduces better than oil; many top illustrators were watercolorists. Upon his return to New York, Teague showed this work to Henry Quinan, the art director for Crowell-Collier’s. Quinan liked the samples and told Teague that he would provide him with all the work he could handle as he established himself in the new medium. I ask myself, why did Teague decide to convert to watercolor at this particular highly uncertain time, unless he had spoken with Quinan before the England trip and had been encouraged to start making the switch? At this point, one can never know the sequence of events – but the question is intriguing as Teague ultimately became known as a preeminent watercolorist.