Donald Teague Biography 4 (1940-1949)

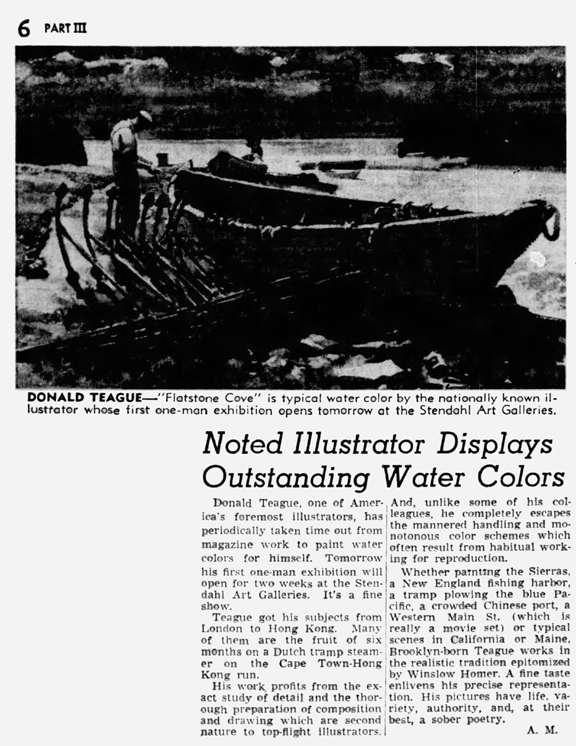

During the 1940’s, despite World War II and the aftermath, Teague prospered. He continued to illustrate for The Post, Collier’s, and other leading magazines. He also continued to pursue his fine art interests, garnering several prestigious national awards, including first prize for watercolor at the National Academy in 1947 and 1949. In 1944, he had his first one-man fine art show at the acclaimed Stendahl Art Galleries in Los Angeles.

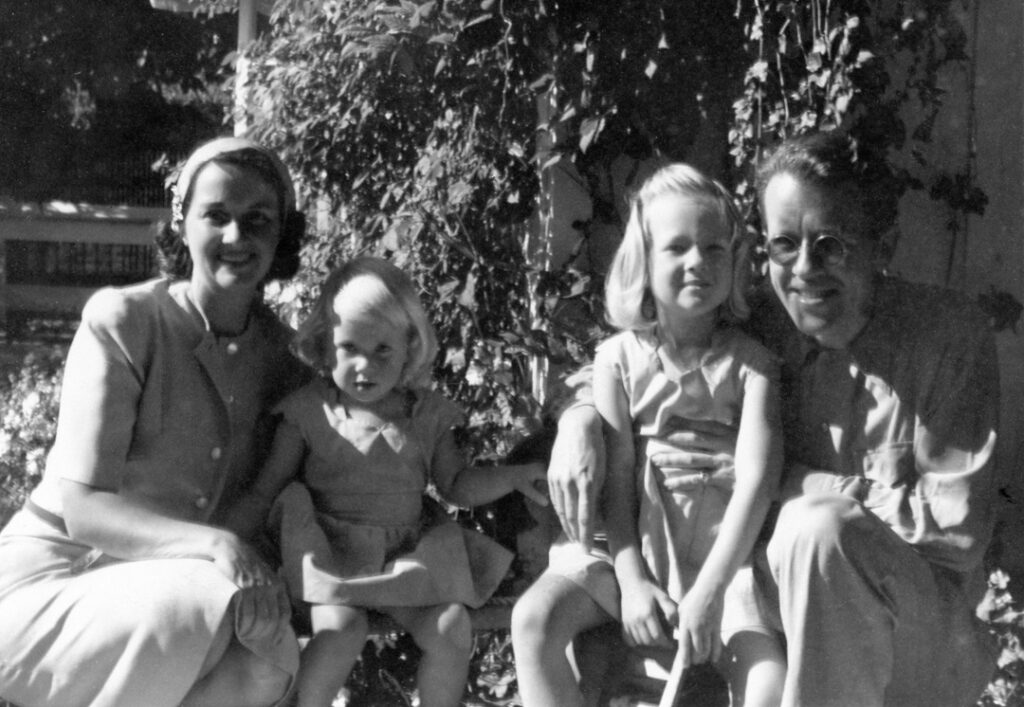

Teague enjoyed a happy family life in Encino. Verna and Don had their first daughter, Linda, in early 1940. Sister Hilary was born on Christmas Day, 1941. Hilary’s arrival was memorable – as Linda described the birth decades later:

My sister, Hilary, was born right after Pearl Harbor during a blackout. With my very pregnant mother stretched across

the backseat of their car, Dad drove in the dark clear across town to Temple Hospital.

The Teagues had a strong family support system in place in Encino. Don’s father and brother lived reasonably nearby. Verna’s parents Harry and Polly moved to Encino from New York so that Polly could be near her daughter and help with the children.

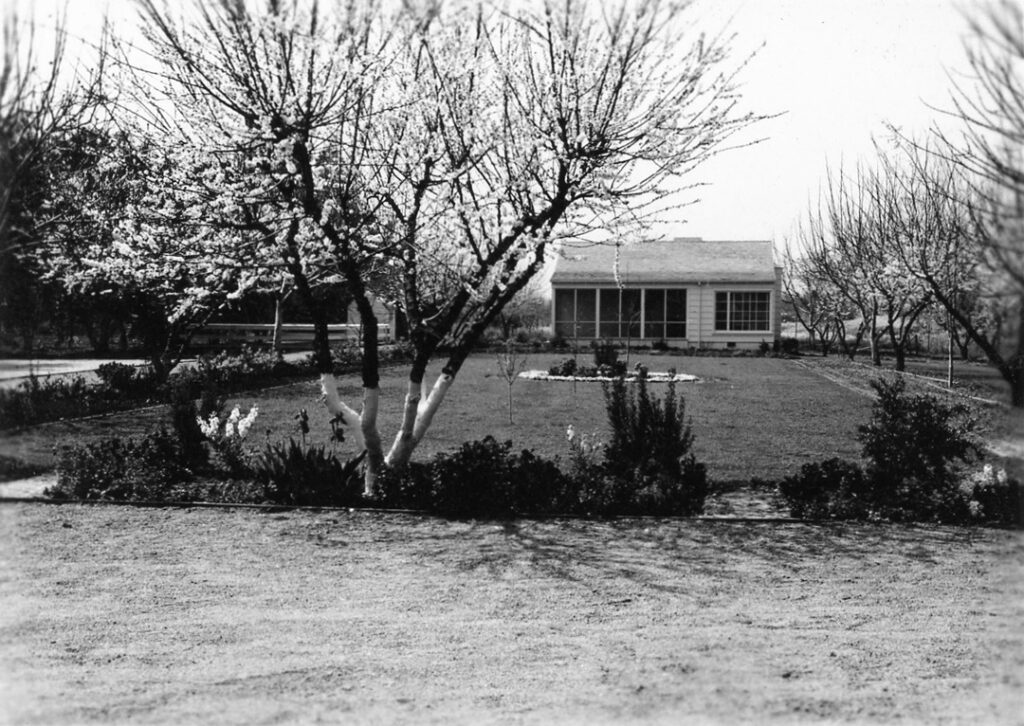

The Teague’s residential lot in Encino was quite deep. Soon after establishing his family in Encino, Teague enlisted his brother Jack to help build a separate studio building toward the back of the lot.

After breakfast, Teague would typically make his way to the studio and start working. He would emerge for meals and other necessities. As Linda described the arrangement:

Dad worked in a studio that he and his brother, Jack, built, that was some distance behind the house. My early memories

include reaching up and ringing a large cast-iron bell that was mounted on a post outside our back door to call him in for a meal or a telephone call.

Toward the end of 1941, an unusual but critical request came in. Teague described the situation as follows:

The Post’s art editor [Pete Martin] said that he would rather not have me work for Collier’s, since they were a major

competitor. I requested that I be allowed to illustrate for Collier’s under a different name, which was agreed to [by Teague’s good friend, Collier’s art editor Bill Chessman]. I chose the name of Edwin Dawes for my Collier’s work, since my father’s name was Edwin Dawes Teague. As I recall, I was the only artist permitted to take that course of action, although there were others who later made the same request. I always thought it a fine piece of irony that on the day the Dawes signature first appeared, six agents called Chessman to find out where the new guy came from and where they could get in touch with him.

And so from mid-1942 on, Teague continued to illustrate for Collier’s, but under a pseudonym. The pseudonym requirement did not carry over to Woman’s Home Companion, nor The American. Teague’s dual identity led to some amusing moments, such as the time Edwin Dawes received a letter from Arthur William Brown, president of the Society of Illustrators, inviting him to join the organization. Dawes responded that since he lived so far from New York City, it would be impossible to participate actively, so he declined the invitation with thanks.

Although Teague’s dual identity as an illustrator is humorous, it is ironic that The Post made the request, as they had let Teague go for seven years during the Great Depression. Working under a pseudonym did nothing to further Teague’s stature as an illustrator while he was alive, nor after. Precious few people knew or know that Edwin Dawes was Donald Teague, and thus do not consider the Dawes output in gauging Teague’s legacy as an illustrator.

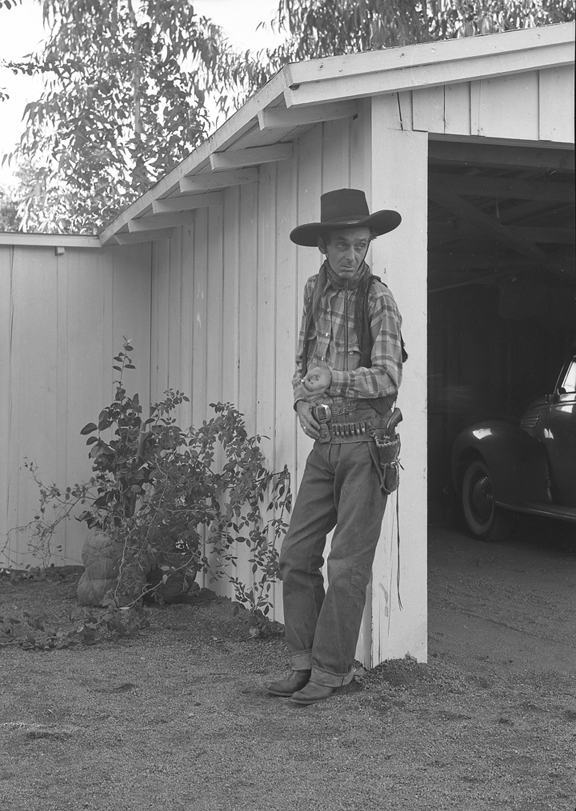

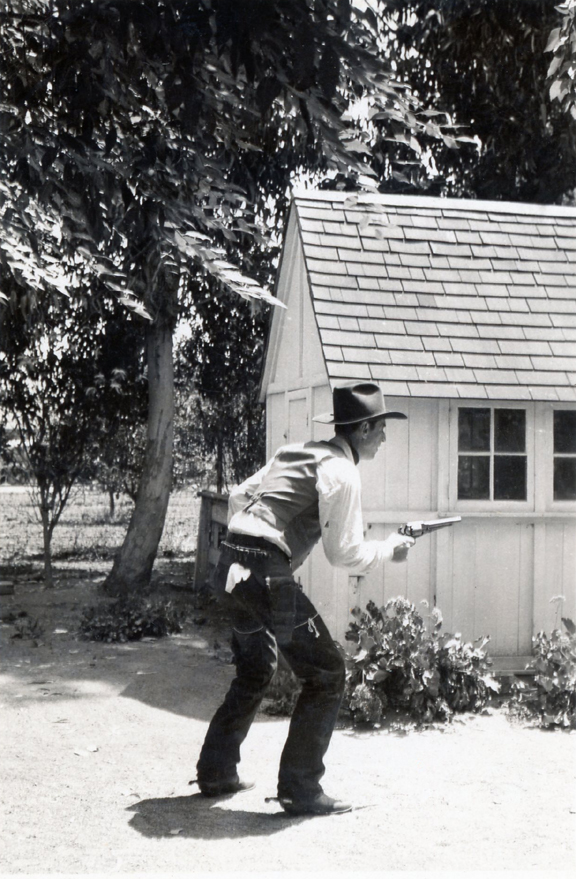

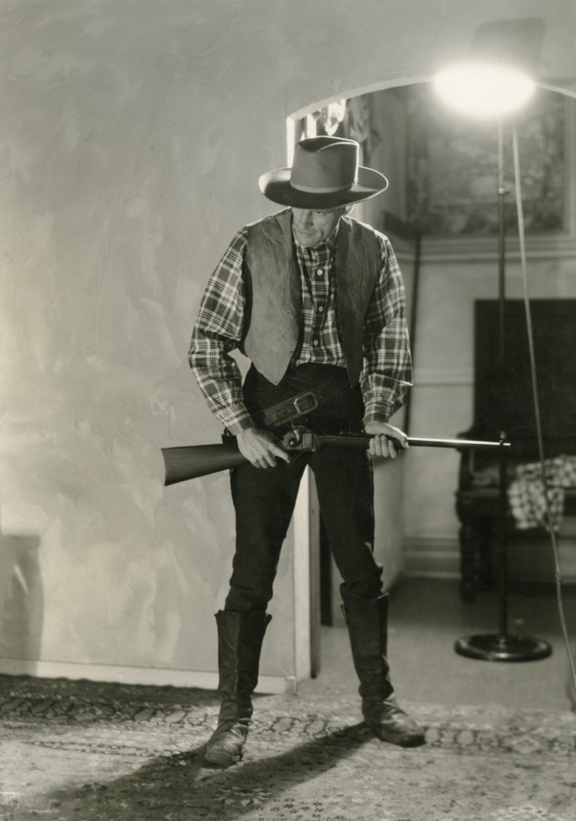

In Encino, Teague gained heavy exposure to the film industry. He adopted many of the processes he observed in his own art-making. In addition to hiring actors, Teague obtained period costumes for them to wear, did his own lighting, and at times even built props for his actors to use or navigate. Over the years, Teague had collected a wide assortment of guns, and he used these as props during shoots. Teague would take still photographs during these sessions, then use them to help get lighting and shadows, clothing folds and the like perfect in his illustrations. Teague’s process enhanced the realism and authenticity of his illustrations. Many of his illustrations from the 1940’s and 1950’s push the boundary between illustration and fine art. This dynamic set him apart from many of his peers, who pursued the minimalist glamour style popularized by Al Parker.

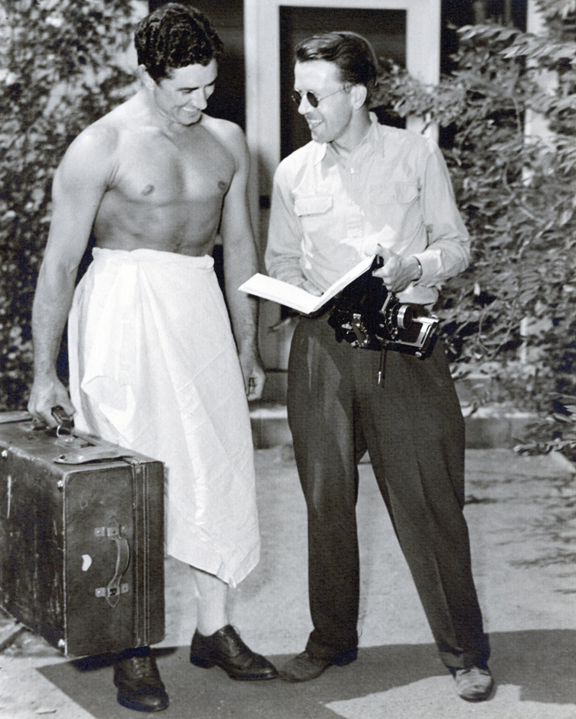

Illustration-related photos taken by Teague at his property are intriguing – one gets the sense that the place was infested with gunslingers and other men of danger. Teague often used western film actors as models for western illustrations. Actor George Bruggeman (who, among other things, doubled for Johnny Weismuller in Tarzan movies) modeled quite a bit for Teague, mostly for non-westerns. In addition to paid actors, Teague leaned on his family to serve as models. Brother Jack served as Teague’s primary model in Encino. Jack was tall, fit and rugged-looking – in short, an excellent model for illustrations. Teague used his brother mostly for non-western assignments. Father Edwin, wife Verna, and daughters Linda and Hilary also occasionally got in on the act. Several photos from Teague’s Encino shoots are posted with the corresponding illustration. A few additional images are presented below.

After a decade of happy years in Encino, in 1949 the Teagues decided it was time to pull up stake and head north. Linda described the scenario as follows:

After World War II was over, people started moving into the San Fernando Valley in droves. The cow pasture at the end of the street was turned into Veteran tract housing. Burbank Boulevard was paved over, and there was talk of a double yellow line down our country lane. That’s when my parents decided to move north. They looked as far as Marin, but finally settled on Carmel for its beauty, proximity to the ocean, and resident artists, writers, cartoonists and so forth. Mom also liked the easy access to San Francisco. Privately, Dad also thought he had escaped from his mother-in-law.

At age 52, Teague entered the next phase of his life and career in Carmel-By-The-Sea.